Strong Third Quarter GDP, with Some Caveats: Is Healthcare the Key to Affordability?

Healthcare inflation should be measured as what we pay for it, not the price of specific items

The third quarter GDP number came in at 4.3 percent, somewhat higher than most analysts had expected. The biggest part of the story was a sharp decline in the size of the trade deficit, which added 1.59 percentage points to the quarter’s growth.

This was not entirely a surprise, even though the size may have been somewhat larger than expected. The story here is that the trade deficit exploded in the first quarter, as households and businesses stocked up in anticipation of the Trump tariffs. That rise subtracted 4.68 percentage points from growth pushing first quarter GDP into negative territory.

The rise in the trade deficit was largely reversed in the second quarter, with the process continuing into the third quarter. The trade for 2025 as a whole is still running above the 2024 level, although it may be somewhat small going forward.

Pulling out trade and inventories to get a measure of core GDP, growth was still a very solid 2.9 percent. Taking the first three quarters as whole, GDP growth averaged 2.5 percent, almost exactly the same as the 2024 pace.

Income Growth Was Slower

GDP growth, which measured GDP on the output side, was somewhat faster than the growth in Gross Domestic Income (GDI), which measured growth on the income side. These are defined as being equal (all costs of the items in GDP are income to someone), so the gap is due to measurement error. GDI grew at just a 2.4 percent rate in the quarter.

Some commentators have noted that the saving rate, which is measured as the share of disposable income that is not consumed, fell to 4.2 percent in the third quarter, a historically low number. This should not be cause for concern. Income is almost always revised upward in later reports. When that happens, the saving rate is likely to be near its recent past levels.

Compensation Growth Slowed

Labor compensation grew at a 3.8 percent annual rate in the quarter. With a 2.8 percent rate of consumer inflation in the third quarter, this translates into real growth of just 1.0 percent. With job growth slowing to a trickle, this may not be that bad a story from the standpoint of workers’ pay, but it will be difficult to sustain a very rapid GDP growth pace if the wage tab is just rising at a 1.0 percent annual rate. This picture will look somewhat better insofar as upward revisions to income show up on the wage side.

Mixed Story on Inflation

The consumer inflation story looks somewhat better in the third quarter, with the year-over-year (YOY) rate for personal consumption expenditures down to 2.6 percent, although the core index was still at 3.0 percent. It is worth mentioning that anyone claiming that tariffs have not had an impact on inflation is not looking at the data in this report.

The price index for consumer durables had been falling since the fourth quarter of 2022. It rose at an average rate of 1.5 percent in 2025. Had the price declines for durables continued the inflation rate would be at, or very close, to the Fed’s 2.0 percent target.

One area on the inflation front that is striking is the sharp rise in prices for investment goods. The deflator for non-residential fixed investment rose at a 5.2 percent annual rate in the quarter. That pushed the overall GDP deflator to 3.8 percent for the quarter, the highest since the first quarter of 2023.

There were sharp price increases in all three categories of investment, with equipment investment leading the way with a 5.8 percent rate of inflation. This is likely in large part due to demand created by the AI bubble, although AI-related investment seems to have slowed in the quarter. Investment in information processing equipment rose at just an 8.4 percent annual rate.

Healthcare Spending Is Rising Rapidly as a Share of Income

As I’ve written in the past, I have never been happy with the “affordability” debate. It never made sense to me that people are upset that prices are high, they care about prices relative to their income. Furthermore, when there is a near consensus about a topic in elite circles, it is almost always wrong.

In the 1980s, after a much sharper increase in prices in the 1970s inflation, no one was talking about prices being high. They were all happy that the rate of inflation had come down to a more manageable pace. I find it hard to believe that people’s views of the economy and the world have changed so much in forty years.

To be clear, I’m sure some people in this country were talking about prices being high back in the 1980s. They just didn’t get their views constantly echoed in the media, as has been the case in the last few years.

Anyhow, I’m going to stick to my old-fashioned view that people primarily care about their wages relative to prices, as in real wages, with an important caveat. We measure healthcare inflation as the rate of increase in cost for the same items. This means it’s an average of the price rise for various types of drugs, surgeries, hospital stays etc.

No one knows or cares about these prices. They care about what they pay for healthcare: for their insurance, their copays, and their out-of-pocket expenses.

We don’t have up-to-date data on out-of-pocket spending on healthcare (my CEPR colleague John Schmitt and former colleague Emma Churchin are putting out a detailed analysis of the recent past), but we can get a sense of where costs have gone from the GDP data.[i]

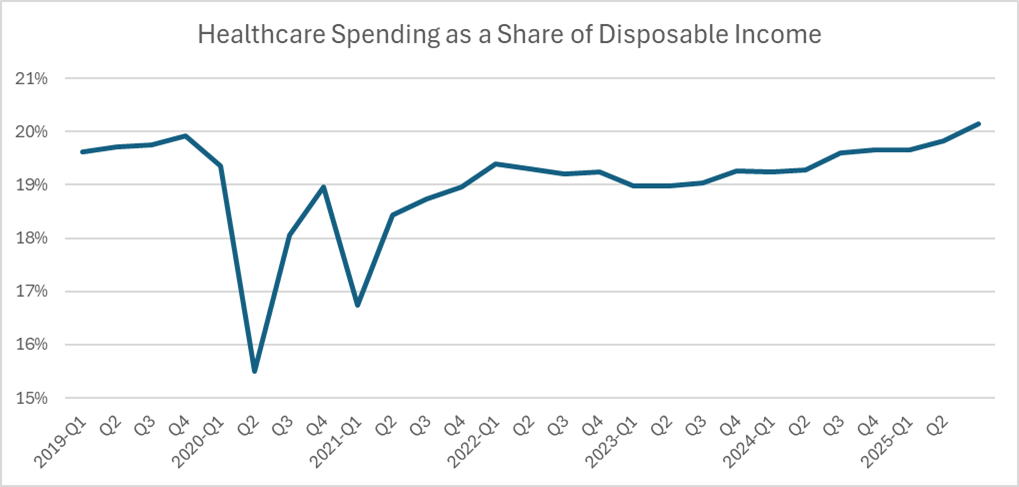

After plunging in the pandemic (people put off regular checkups and other non-essential care) healthcare costs began to rise rapidly in 2023 and have continued to rise into this year. The healthcare spending share of disposable income has risen by more than a percentage point in the last two years.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis.

Again, we need to know more concretely about how this translates into money out of people’s pockets. Most of this spending comes from government programs or employer-provided insurance. But it is virtually certain that the out-of-pocket share has risen as well, and with the end of the enhanced premium subsidies in the ACA, it is about to rise much more rapidly in 2026 for millions of households.

Anyhow, this is a source of inflation that people do feel in their pocketbooks that is not picked up in the CPI. If spending on healthcare is rising, maybe due to more drugs and scans rather than higher prices, people are likely to still see it as inflation, even if the Bureau of Labor Statistics doesn’t count it that way.

[i] This calculation sums lines 128, 179, and 282 from NIPA Table 2.4.5U and divides by Line 27 from Table 2.1.

Strong analysis linking healthcare spending growth to real affordability pressures. The distinction between CPI-measured inflation and actual out-of-pocket costs is critical, most people experience healthcare as a rising share of disposable income regardless of whether specific item prices are stable. The timing matters too, that 1%+ increase in healthcare's share ofthe income over two years compounds when combined with wage growth barely outpacing overall inflation. dunno if the ACA premium subsidy cliff in 2026 is getting enough attention given how much it'll amplify this trend.

Healthcare is certainly a pillar if not the largest pillar of affordability since it consumes about 18% of GDP. In the last analysis, government and employer subsidies come from the public writ large, and since we spend at least 5% of GDP too much for the healthcare we're getting, it is a key/cornerstone of affordability. Because of the way we pay for it, far too much of that cost is hidden for most of us, which makes it harder to generate the political urgency necessary to radically improve our system.